Kansas City Research Site

KU researchers are piloting an empirical data collection model in the Kansas City metro area. Kansas City is a major metropolitan area in the heartland, known as a focal point of human trafficking, with emblematic migration patterns for domestic and international labor forces. Our scan of organizations in the Kansas City area working with vulnerable populations has included women's shelters, LGBT youth organizations, faith-based organizations, migrant labor organizations, ESL classes, members of the government, and social service providers.As researchers, we are aware of the multiple levels re-victimization that may happen when someone is identified as a trafficking survivor. We are also aware many survivors are in the process of rebuilding their lives, and reliving their experiences for research investigation may be disruptive. Instead of focusing our research on trafficked persons who were willing to be interviewed, we focused on a broad range of organizations and service providers in order to capture a comprehensive understanding of vulnerability and resilience. These organizations encounter trafficked persons, but they also encounter clients that are vulnerable to multiple forms of exploitation, not limited to trafficking. In understanding the basket of factors that can lead to vulnerability, we hope to find interventions and strategies that can prevent future exploitation.

In total over 70 such organizations have been identified in our scan. In September 2013, our team of researchers began contacting these organizations to set up interviews. The data collected through these semi-structured interviews have been used to begin identifying: 1) vulnerable groups and 2) risk factors as well as resiliency factors.

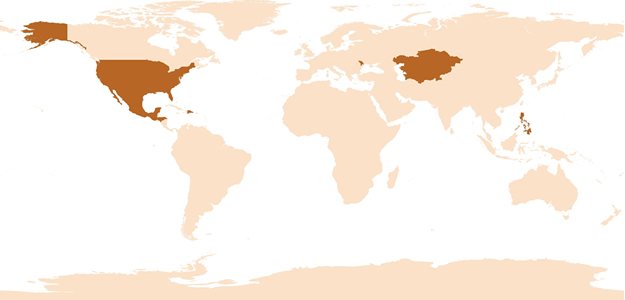

Countries of Origin

This project focuses on the Kansas City metro area, yet trafficking is a global issue, as indicated by the vast span of countries of origin. Local service providers worked on U.S. domestic cases as well as cases with clients from Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Moldova, Ukraine, the Philippines, the Dominican Republic, and former Soviet countries.Community and Individual Risk Factors

Certain risk factors associated with sex trafficking and labor trafficking appeared consistently in our interviews, matching with the existing research in the field.Confirmation of Existing Research

The research in the field has found that individuals who have been trafficked sexually have histories of poverty and early childhood trauma, such as physical or sexual abuse. The literature also finds that labor trafficking is greatly affected by citizenship, as undocumented individuals are more vulnerable to be trafficked. Language deficiencies and illiteracy are also contributing factors, as individuals with a limited knowledge of English are more susceptible to exploitative labor practices. The ASHTI project in the Kansas City Metro area confirms these major findings. At the same time, service providers in our study were adamant that anyone can be trafficked, regardless of background or privilege—there is no one typical trafficking victim.

New Findings

Violence During Trafficking: While the existing research discusses the violence found in sex trafficking, there is less attention to violence in the labor trafficking sector. Our research indicates that sex trafficking and labor trafficking are violent systems that involve both physical and sexual abuse. Our interviews indicated that service providers who encounter labor trafficking also encounter persons who have experienced a high degree of violence, including rape and sexual abuse, in transit to the US or during their period of forced labor in the US. This violence may have been overlooked in other studies because the abuse (particularly sexual) is often unspoken or dismissed. The service providers in this study have indicated they are now aware and looking for this history of violence among their clients. This is a vital finding where service providers are ahead of much of the scholarship in the field.

Poverty: Poverty continues to be a pertinent risk factor. Trafficking is a money-driven industry, and those living in poverty often lack the institutional and personal resources to cope with their vulnerabilities. While any one of any socio-economic class can be trafficked, people who are not in poverty often have more personal resources to assist them in transitioning out of vulnerability.

Foster Care System: Our research finds that individuals within the foster care system are in a position of increased vulnerability, especially when aging out of the system. Without a solid support system—on individual or institutional levels—to rely upon after exiting the system, foster children are more likely to have housing and economic insecurities that perpetuate risk factors such as homelessness.

Lack of Family Identity: Interviews revealed that even if youth or adult survivors were not part of the foster care system, they were at an increased risk of vulnerability if they lacked a solid attachment to some form of family life. Trafficked children often had unstable home situations where they moved from family member to family member and did not have a consistent adult or guardian. They also faced instability in terms of home life, with drug use, poverty, and cyclical homelessness creating uncertainty in their lives.

LGBT Status: LGBT individuals find themselves in similar positions of vulnerability if they come out to an unsupportive family or find themselves in a hostile community. Though the literature surrounding trafficking does not discuss this issue in depth, service providers in the ASHTI study consistently mentioned members of the LGBT community as a frequently served population. LGBT youth are particularly vulnerable: if an underage child is kicked out of their house for identifying as queer, their options for housing and financial support are incredibly limited, placing them in an extremely vulnerable position, susceptible to exploitation like “safety sex” for food and shelter.

Demand Forces: The participants in this study frequently discussed the problematic issue of demand for trafficked persons – either the demand for sex or labor trafficking – that they encountered as one of the biggest contributing risk factors they faced. They brought this idea forward without prompting, and it was a new dimension to the teams conceptualization of contributing factors. The issue of demand is difficult to navigate: as long as individuals wish to exploit trafficked persons, there will be a trafficking industry. Combating this would require larger structural changes, such as modifying strict gender norms, or race and class privileges. For example, shifting attitudes about men’s access to women’s bodies could also shift the demand for sex-trafficked individuals, but this requires an ideological change within society as a whole.

Protective Factors

The importance of protective factors—certain influences or structures that predict resilience—also emerged in our interviews.

Education: Education was one of the most consistent and significant protective factors that appeared across interviews. If an individual remained enrolled in school, identified with specific teachers or staffers, or saw education as a pathway out of poverty, they remained less vulnerable to exploitation than their peers without these beliefs or relationships. Schools provide support systems for those who might not have them outside the classroom and create an environment where home-life pressures can be temporarily alleviated. Service providers also see schools as a place to combat the misconceptions surrounding human trafficking. If schools can intervene early, teaching students about trafficking from a young age, then more students will be aware of the fraud, force, and coercion that can take someone from a position of vulnerability to one of exploitation or trafficking.

Labor Rights Education or Organizations: When discussing protective factors for persons in labor trafficking, service providers saw connections to worker’s rights and educational organizations as a way to combat the vulnerability that comes with an undocumented status. One service provider discussed how a labor union in the United States recruited members in Mexico, who were guaranteed membership upon legal entry. Labor unions are able to increase their membership and offer a protective affiliation for those immigrating into the United States. Institutionalized services for members of the labor force that include language training, rights-based education or information, and information on trafficking violations would give victims access to the skills and information they need to come forward more confidently.

NEXT STEPS

In moving forward with the ASHTI project, we first plan to expand our interviews to address our new findings. Based on the complexity of the issue of education— a lack of education indicates risk and a focus on education indicates resilience—we will move forward in interviewing ESL classes, adult education centers, and student resource teams in public schools. Since many anti-trafficking efforts are housed within religious institutions, we will continue interviewing church leaders in the community. Though our project is focused on prevention, speaking to those involved in the prosecution of trafficking offenses—for example, task force leaders in local police units—remains an important final step in our interview process.

Based on our interview data, we intend to geographically place our findings onto the Kansas City metro area, mapping the terrain of trafficking and vulnerability. Using general indicators of risk—such as poverty, health care, insurance access, and school truancy—we can see if there are certain physical spaces where more of these risk factors accumulate. We also hope to identify social service deserts where it is particularly difficult for a vulnerable person to access assistance. Additionally, using service providers’ locations—provided they are not confidential—we can determine if there are general service deserts, or areas in Kansas City that do not have accessible medical clinics, soup kitchens, domestic violence shelters, ESL classes, and more.

Given our public health approach, creating practical tools and curricula is a crucial project goal. We are working on making our interviewing tools accessible online, so future researchers can utilize our framework for their own projects. Additionally, we have contacted the Kansas Attorney General’s Human Trafficking division to open a dialogue about what is needed in a human trafficking curriculum for a variety of institutions, such as schools, state offices, police stations, and medical clinics.